Batteries Included. That's the Python motto. Python comes with a huge collection of standard libraries. Standard libraries are packages of code that come with Python to help you solve common tasks. Why reinvent the wheel every time?

What follows is a selection of handy tools from Python's standard libraries. For a full list of the Python standard libraries check here.

Frequently, we will need to deal with dates. First, let's just define a date for June 17, 2015:

>>> import datetime

>>> start = datetime.datetime(2015, 6, 17)

>>> print(start)

'2015-06-17 00:00:00'Now let's define a datetime object for a date and time 6:30 PM on July 17, 2015:

>>> from datetime import datetime

>>> end = datetime(2015, 7, 17, 18, 30)

>>> print(end)

'2015-07-17 18:30:00'If you have a pre-existing datetime object, you can pull the individual pieces of information out of it pretty easily:

>>> end = datetime(2015, 7, 17, 18, 30)

>>> end.year

2015

>>> end.month

7

>>> end.day

17

>>> end.hour

18

>>> end.minute

30

>>> end.second

0We can even use the standard comparison operators compare the two dates:

>>> start < end

True

>>> start > end

False

>>> start <= end

True

>>> start >= end

False

>>> start == end

False

>>> start != end

TrueNow let's use a for loop and a timedelta to print out ever day of Ramadan (2015):

>>> day = start

>>> while day < end:

... print(day)

... day += datetime.timedelta(days=1)

'2015-06-17 00:00:00'

'2015-06-18 00:00:00'

'2015-06-19 00:00:00'

...

'2015-07-17 00:00:00'If you do a help(datetime.timedelta), you will find out that we can set up a timedelta in units of: days, seconds, or microseconds.

If you want to get the current date and time, use .now():

>>> from datetime import datetime

>>> datetime.now()

datetime.datetime(2015, 3, 14, 9, 26, 53, 589792)Now, that loop above is a pretty good start, but those print outs are a little ugly. I'd like it if they were formatted more like June 17, 2015. To do this, we use the strftime function:

>>> start.strftime('%b %d, %Y')

'Jun 17, 2015'OR we could format the dates in the a more computer-friendly format:

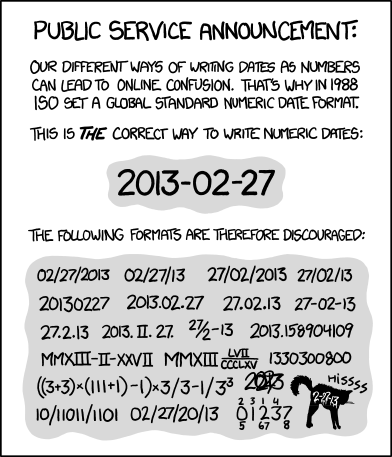

>>> end.strftime('%Y-%m-%d')

'2015-07-17'This is the ISO 8601 format and it is ideal for working with computers. Notice that if you alphabetize a list of these strings, the dates will be in chronological order.

That strftime looks really useful. You can find a complete listing of all of the datetime formatting codes here.

There's actually one more Really useful thing we can do with these date formmating strings. Imagine we are reading in a text file and we hit a bunch of text that is meant to represent dates and times. We can use strptime to create a datetime object from a string:

>>> from datetime import datetime

>>> pi_day = '2015-03-14'

>>> d = datetime.strptime(pi_day, '%Y-%m-%d')

>>> print(d)

datetime.datetime(2015, 3, 14, 0, 0)The math library in Python has a lot of typical functions built in.

It has sin, cos, tan, and of course pi

>>> from math import cos, pi, sin, tan

>>> sin(0)

0.0

>>> sin(pi)

0.0

>>> cos(0)

1.0

>>> cos(pi)

-1.0

>>> tan(0)

0.0

>>> tan(pi)

0.0It also has asin, acos, atan, and sinh, cosh, tanh, asinh, acosh, atanh.

All of the above work in radians. It might be helpful to know you can convert from degrees to radians using math.radians:

>>> from math import cos, radians

>>> radians(0)

0.0

>>> radians(90)

1.5707963267948966

>>> radians(180)

3.1415926535897931

>>> cos(radians(180))

-1.0It can also do sqrt and arbitrary powers (pow):

>>> from math import pow, sqrt

>>> sqrt(4)

2.0

>>> pow(2, 3)

8.0

>>> pow(4, 4)

256.0It can also do various kinds of exponentials and logarithms:

>>> from math import e, exp, log, log10

>>>

>>> exp(1)

2.718281828459045

>>> exp(2)

7.38905609893065

>>> log(1)

0.0

>>> log(10)

2.302585092994046

>>> log(100)

4.605170185988092

>>> log(1, e)

0.0

>>> log(10, e)

2.302585092994046

>>> log(100, e)

4.605170185988092

>>> log10(10)

1.0

>>> log10(25)

1.3979400086720377You might have noticed above we imported modules from datetime and math slightly differently. Just to be clear, both of the following options are valid Python code, and will have the same results:

>>> from math import cos, pi

>>>

>>> cos(pi / 4)

0.7071067811865476or

>>> import math

>>>

>>> math.cos(math.pi / 4)

0.7071067811865476People will have their preferences, but the results are the same.

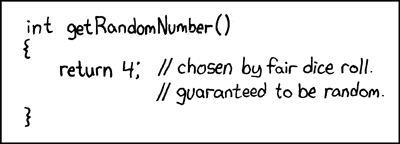

How not to generate random numbers:

There are a lot of different ways to generate pseudo-random numbers in Python. But here is a short introduction to the three you can use to generate all the other functionality in the library.

The most general and useful method is the basic random, which generates a float between zero and one:

>>> from random import random

>>> random()

0.9719607738140819

>>> random()

0.8947058583583551

>>> random()

0.1309924455836774Similarly, randint generates a random integer between two bounds:

>>> from random import randint

>>> randint(1, 99)

27

>>> randint(1, 99)

68

>>> randint(1, 99)

13Another really useful tool is choice, which will select a random item from a list:

>>> from random import choice

>>> x = [1, 'think', 3, 4, 5]

>>> choice(x)

1

>>> choice(x)

5

>>> choice(x)

'think'Another tool that is helpful, particularly for statistical studies, is the ability to randomly change the order of the elements of a list with shuffle:

>>> from random import shuffle

>>> lst = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e']

>>> shuffle(lst)

>>> lst

['b', 'e', 'a', 'c', 'd']

>>> shuffle(lst)

>>> lst

['d', 'a', 'e', 'b', 'c']One of people's main complaints about Python is that it isn't as fast as C. But it can be faster if you try. The first thing you will need to try to make your Python code faster is a way to time how long the code takes to run. That way, if you make some modification to your code, you can time the original version and your new version to see which is fastest. That is, generally, the only way to prove that you've made your code faster.

Python's timeit library is an easy way to time your code without having to change it. For instance, let's say we have a function we are trying to speed up:

>>> def build_counting_list(n):

... '''build a list of lists where the elements are:

... [1]

... [1, 2]

... [1, 2, 3]

... and so on.

... '''

... counting = []

... for i in range(1, n):

... counting.append(range(1, i + 1))

... return countingNow, to time that function, we run it 1 time:

>>> from timeit import timeit

>>> timeit(str(build_counting_list(4)), number=1)

5.0067901611328125e-06There are two things to understand about that last line. First off, we have to encapsulate our function call with str(), because timeit takes strings. And second of all, that number=1 means we only do the thing we're timing once. If we want to get a more accurate count, we might run the process 10,000 times:

>>> timeit(str(build_counting_list(100)), number=10000)

0.5770218372344971Sometimes, if you are running timeit on something inside a script (.py file), you will have to do something just a little bit funnier to get timeit to work:

from timeit import timeit

def build_counting_list(n):

...

t = timeit('from __main__ import build_counting_list;build_counting_list(100', number=10000)

print(t)That timeit takes strings is a little strange. But it also allows us to write our code directly into the timeit statement:

>>> timeit('range(100000)', number=1000)

1.1704330444335938Timeit is a really handy tool. Maybe it takes a little getting used to, but it is a lot more accurate than most other ways you might try to mock up to time your code.