There are a lot of different kinds of databases: SQL, MySQL, Postgres, Mongo, etc. And each different type of database has it's own Python library. In this lecture we will look at MySQL databases using the MySQLdb library. MySQL is one of the most popular database choices for medium-sized projects today, and it is open-source. If you're interested, you can look here for a listing of the most popular database interfaces in Python.

Most databases are servers or services that are run on your computer. And that is no different for MySQL, look here for instructions on installing and starting a MySQL server on your computer. You will also need to install the mysql-python library. If you are using Anaconda, this should be as easy as:

conda install mysql-python

There are many books and entire courses covering the topic of databases. It is very important to understand that this is just a light introduction. The purpose of this lecture is not to teach database theory, it is only to explain how to use a single Python database library.

MySQL is a relational database. Broadly speaking, that means the data is arranged into tables by rows (records) and columns (attributes).

In MySQL, to create a connection to our database server, we need to use our credentials:

import MySQLdb

con = MySQLdb.connect(host='localhost', user='my_user_name', passwd='my_secret')Note that you don't actually need to write host= or user=, these items are always in the same order. For now, we will write them explicitly, until they become more familiar.

To run almost any code against your database, you will need to create a cursor:

cursor = con.cursor()At the end of your work, it is important to close your database server connection:

con.close()Whether you want to create, modify, or retrieve information from a MySQL table, the process will always be the same:

- connect to the database

- create a cursor

- execute MySQLdb code

We want to create the database shown in the diagram above. To do that, we need to create our database connection, create a cursor, and run our first query against the database:

import MySQLdb

con = MySQLdb.connect(host='localhost', user='my_user_name', passwd='my_secret')

cursor = con.cursor()

cursor.execute('CREATE DATABASE `secret_agents`;')

cursor.execute('USE secret_agents';)The CREATE command is clear, but the USE command is not so obvious. We can CREATE as many databases as we want, but in order to go inside that database and interact with it, we need to execute a USE command first. And later, if we want to interact with a different database, we will execute another USE command.

For instance, if I wanted to create the agents table above I might do:

cursor = con.cursor()

cursor.execute('''CREATE TABLE `agents` (

`agentID` int(11) NOT NULL auto_increment,

`code_name` varchar(3) NOT NULL default '007',

`name` varchar(30) NOT NULL default 'James Bond',

PRIMARY KEY (`agentID`))

''')First notice that a cursor was created using .cursor(), we ran the MySQL code against the database using .execute().

You may also noticed something very strange. What is all this CREATE TABLE gobbly gook? That's not Python code! Good observation; that is not Python code. When we interact with the database, we do so with a variant of the popular SQL database langauge called MySQLdb. It might seem unfair that now you have to learn a whole new programming language. But there's nothing for it. If you want to deal with databases, you need to learn to talk to them on their own level.

What the above MySQLdb code did is pretty simple, it created a new table (using CREATE TABLE with three columns:

- agentID

- code_name

- name

These columns all have types INT and VARCHAR. Though there are other possibilities, like DATETIME, TIMESTAMP, INT, and many more. And one of them is defined as the PRIMARY KEY. A key is a unique identifier in a table. You can have a table without a key column, but it's good practice to include them unless you have a very good reason not to.

Right now the table is empty, so let's add values using INSERT. There's obviously one agent we can add:

cursor.execute('''INSERT INTO agents(agentID, code_name, name)

VALUES(%s, %s, %s)''', (1, "007", "James Bond"))But we wouldn't be much of an agency with only one agent, so let's run several INSERT statements at the same time:

# Only one female agent? We're really not much of an agency.

other_agents = [("001", "Edward Donne"), ("002", "Bill Fairbanks"),

("003", "Jack Mason"), ("004", "Scarlett Papava"),

("005", "Stuart Thomas"), ("006", "Alec Trevelyan"),

("008", "Bill")]

cursor.executemany('''INSERT INTO agents(agentID, code_name, name)

VALUES(%s, %s, %s)''', other_agents)Notice here that we made several .execute() statements at once by passing a list as a secondary argument to .executemany().

For this exercise, let's create another table that lists the status of all of our agents (see the diagram above):

cursor.execute('''CREATE TABLE `status` (

`agentID` int(11) NOT NULL auto_increment,

`status` varchar(30) NOT NULL default 'Inactive',

PRIMARY KEY (`agentID`))

''')And fill it with data (all our agents are currently active).

for i in range(1, 10):

cursor.execute('''INSERT INTO status(agentID, status)

VALUES(%s, %s)''', (i, "Active"))Now let's say one of our secret agents dies and we want to update their status. We would do so using the SQL keyword UPDATE:

cursor.execute('''UPDATE status SET status = %s WHERE agentID = %s ''',

("Deceased", 7))Notice here we also used the MySQL keyword WHERE. This fun little piece of syntax allows us add a conditional case so we can set (or get) just certain fields in our table.

Let's say we notice a mistake in the database. In this case, we only have 8 agents but there is a ninth agent listed in the status database. Well, if enough time has passed, we won't be able to use .rollback(). But we can delete any database entry we want using the DELETE keyword.

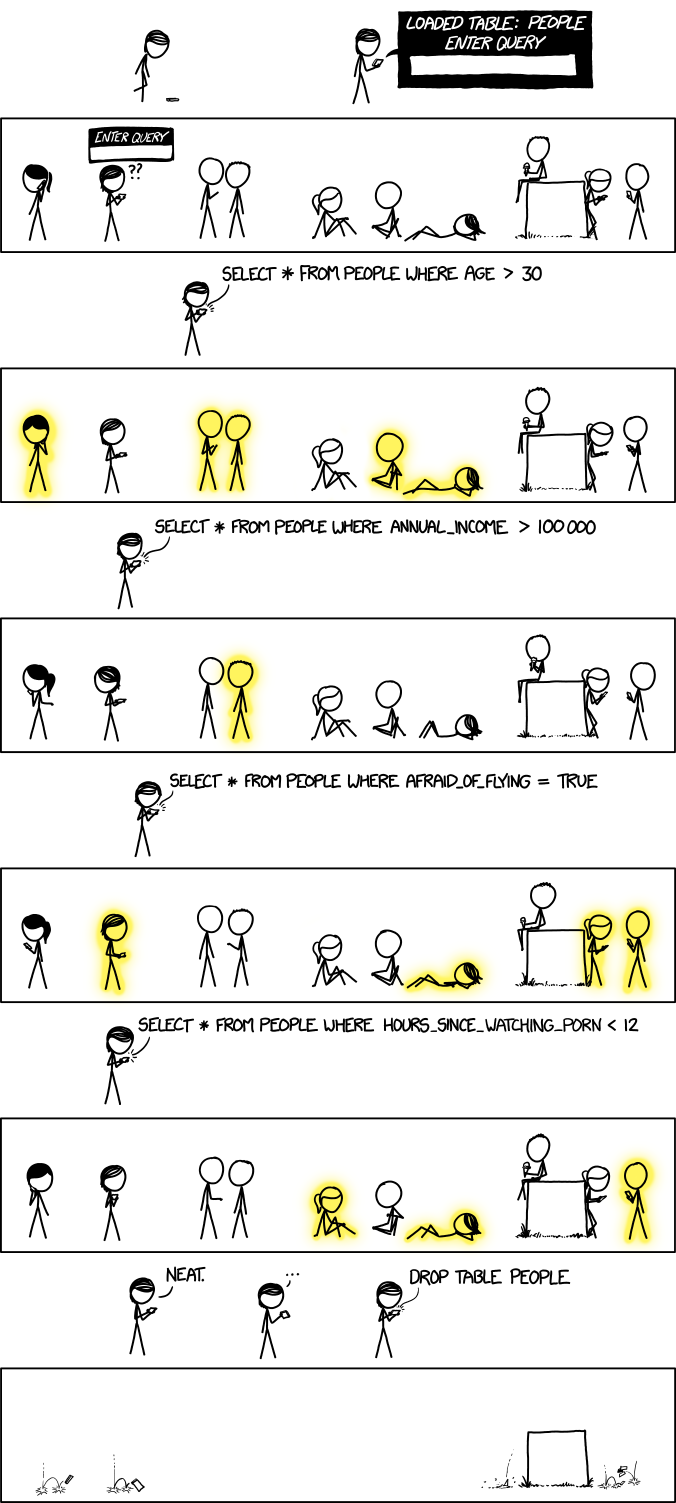

cursor.execute("DELETE FROM status WHERE agentID=9")Databases wouldn't be very helpful if we couldn't get information out of them. The most basic way to "query" data from a database is using the SELECT keyword. Let's use SELECT to "query" all of the active agent ids from the status table.

cursor.execute('SELECT agentID,status FROM status WHERE status="Active"')

active_agent_ids = cursor.fetchall()There are a couple of things to notice here. First of all, we used .fetchall(), because the command we are executing in the database is returning information. The values returned are always in the form of tuples, where each column is an item in the tuple. In this case, active_agent_ids is a list of tuples.

If we just wanted to get one value that met the conditional criteria of our query, we could use .fetchone() instead of .fetchall():

cursor.execute('SELECT agentID,status FROM status WHERE status="Active"')

active_agent_id = cursor.fetchone()

print(active_agent_id)

# (1, "Active")Above, we listed all of the columns we wanted to pull from the table explicitly by saying SELECT agentID,status FROM. But it is frequently the case that we will want to pull all the columns from a table, so there is a special syntactic sugar for that. The following two queries are exactly the same:

cursor.execute('SELECT agentID,status FROM status WHERE status="Active"')

cursor.execute('SELECT * FROM status WHERE status="Active"')In the above SELECT queries, we are returning every row in the table that matches our WHERE clause. This is fine here, because we only have 8 agents. But imagine if you are pulling data from a table with millions of rows. And maybe you just want to take a look at an example row to examine the data format. It would be nice to have the power to just pull a couple of rows. To do so, we use the LIMIT keyword:

cursor.execute('SELECT * FROM status WHERE status="Active" LIMIT 1')

active_agent_ids = cursor.fetchall()

print(active_agent_ids)

# (1, "Active")Sometimes we want to remove an entire table (not just a single entry like we did with DELETE). To do so, use DROP.

First, let's create a table to delete:

cursor.execute('''CREATE TABLE `home_addresses` (

`agentID` int(11) NOT NULL auto_increment,

`address` varchar(90) NOT NULL default '',

PRIMARY KEY (`agentID`))

''')And we can add a row to that table:

cursor.execute('''INSERT INTO home_addresses(agentID, address)

VALUES(%s, %s)''',

(3, 'Highclere Park\nNewbury, West Berkshire RG20\n9RN'))Well, we probably shouldn't save the home addresses of our secret agents. If someone gets ahold of this database, they'd all be in trouble. So let's DROP that whole table.

cursor.execute('''DROP TABLE home_addresses''')Done. Our agents don't exist.

A Join is a special kind of query. As the name suggests, a join query returns a combination of two tables. As you can imagine, there are a lot of ways you might want to combine two tables of data. You probably want to match at least one column in both tables, and then based on this match, return some set of columns from both tables.

The SQL language defines three types of joins: inner, cross, and outer.

Earlier, we created a list of all the agents who are currently active. That query worked fine, but it only returned the agent IDs, not there names. That's inconvenient, but we could do a slightly more complicated SELECT query to get their names from the other table:

cursor.execute('SELECT code_name, name FROM agents, status WHERE ' +

'agents.agentID = status.agentID and status.status="Active"')

active_agents = cursor.fetchall()

print(active_agents)Which returns:

[(u'007', u'James Bond'), (u'001', u'Edward Donne'), (u'002', u'Bill Fairbanks'),

(u'003', u'Jack Mason'), (u'004', u'Scarlett Papava'),

(u'005', u'Stuart Thomas'), (u'008', u'Bill')]Perfect, now we see all seven active agents. But notice the use of the and keyword above, it allowed us to make a much more complicated query. The key is that it allowed us to query two different tables, and match a single column in each using: agents.agentID = status.agentID. These kinds of queries are so common, that SQL / MySQL defines a special keyword to help you write them faster: JOIN. Using our new keyword, we would write the above query as:

cursor.execute('SELECT code_name, name FROM agents JOIN status ON ' +

'agents.agentID = status.agentID WHERE status.status="Active"')

active_agents = cursor.fetchall()

print(active_agents)The above join is called an "inner join", and would typically be written as INNER JOIN in SQL. But the MySQL default join is INNER, so that keyword can be left off.

The CROSS JOIN is the least-common join, but probably the easiest to understand. It creates a combination of every record in the left table with every record in the right table. For instance, if we wanted to combine the agents and status tables, we could do:

cursor.execute('SELECT code_name, status FROM agents CROSS JOIN status')

big_mess = cursor.fetchall()

print(big_mess)This would return:

[(u'007', u'Active'), (u'007', u'Active'), (u'007', u'Active'), (u'007', u'Active'),

(u'007', u'Active'), (u'007', u'Active'), (u'007', u'Deceased'), (u'007', u'Active'),

(u'001', u'Active'), (u'001', u'Active'), (u'001', u'Active'), (u'001', u'Active'),

(u'001', u'Active'), (u'001', u'Active'), (u'001', u'Deceased'), (u'001', u'Active'),

(u'002', u'Active'), (u'002', u'Active'), (u'002', u'Active'), (u'002', u'Active'),

(u'002', u'Active'), (u'002', u'Active'), (u'002', u'Deceased'), (u'002', u'Active'),

(u'003', u'Active'), (u'003', u'Active'), (u'003', u'Active'), (u'003', u'Active'),

(u'003', u'Active'), (u'003', u'Active'), (u'003', u'Deceased'), (u'003', u'Active'),

(u'004', u'Active'), (u'004', u'Active'), (u'004', u'Active'), (u'004', u'Active'),

(u'004', u'Active'), (u'004', u'Active'), (u'004', u'Deceased'), (u'004', u'Active'),

(u'005', u'Active'), (u'005', u'Active'), (u'005', u'Active'), (u'005', u'Active'),

(u'005', u'Active'), (u'005', u'Active'), (u'005', u'Deceased'), (u'005', u'Active'),

(u'006', u'Active'), (u'006', u'Active'), (u'006', u'Active'), (u'006', u'Active'),

(u'006', u'Active'), (u'006', u'Active'), (u'006', u'Deceased'), (u'006', u'Active'),

(u'008', u'Active'), (u'008', u'Active'), (u'008', u'Active'), (u'008', u'Active'),

(u'008', u'Active'), (u'008', u'Active'), (u'008', u'Deceased'), (u'008', u'Active')]Of course, in this case, the result of the cross join is not very meaningful. As you can imagine, if both left and right tables get large, the CROSS JOIN can produce absurdly large outputs. BUT, it is one of the standard tools of SQL. Maybe you'll find a good use for it one day.

Finally, we have the OUTER JOIN. The SQL language, actually defines three types of OUTER JOIN: LEFT, RIGHT, and FULL, but MySQL only supports the LEFT and RIGHT varieties. In any case, a "LEFT" OUTER JOIN in MySQL is one where the records from two tables are matched, but all the records in the left table are kept, even if they found no match in the right table.

In order to test this out, let's make a new table to keep the licenses of our agents:

cursor.execute('''

CREATE TABLE `licenses` (`id` int(11) NOT NULL auto_increment,

`agentID` int(11) NOT NULL default 1,

`license` varchar(90) NOT NULL default '',

PRIMARY KEY (`id`));

''')And let's add some data to the table:

cursor.execute('INSERT into licenses(id, agentID, license) VALUES(1, 1, "License to Kill")')

cursor.execute('INSERT into licenses(id, agentID, license) VALUES(2, 4, "License to Kill")')

cursor.execute('INSERT into licenses(id, agentID, license) VALUES(3, 1, "License to Tango")')Now let's peform a LEFT JOIN to pull out all of the licenses for our agents, along with the agent names.

print(' - Retrieve all of our agent licenses, along with the agent names.')

cursor.execute('SELECT code_name,name,license FROM agents LEFT JOIN' +

'licenses on agents.agentID = licenses.agentID')

licenses = cursor.fetchall()

print(licenses)And we get back a full listing of our agent licenses:

[('007', 'James Bond', 'License to Kill'), ('007', 'James Bond', 'License to Tango'),

('001', 'Edward Donne', NULL), ('002', 'Bill Fairbanks', NULL),

('003', 'Jack Mason', 'License to Kill'), ('004', 'Scarlett Papava', NULL),

('005', 'Stuart Thomas', NULL), ('006', 'Alec Trevelyan', NULL),

('008', 'Bill', NULL), ('009', 'Evelyn Salt', NULL)]We really need to get more of our agents up-to-date on their licenses.

For a nice overview of all the types of joins in MySQL, check here.

The above JOIN query returned all of our agents, and their licenses. And that might be what we want. However, we might also have just wanted to return only the non-NULL licenses from the right table, along with the agents names and code names. For this, we could do a very similar query, but using a RIGHT JOIN.

print(' - Retrieve all of our non-NULL agent licenses, along with the agent names.')

cursor.execute('SELECT code_name,name,license FROM agents RIGHT JOIN' +

'licenses on agents.agentID = licenses.agentID')

licenses = cursor.fetchall()

print(licenses)And this would return something a little more useful:

[('007', 'James Bond', 'License to Kill'),

('007', 'James Bond', 'License to Tango'),

('003', 'Jack Mason', 'License to Kill')]Of course, we could have gotten the same result using a LEFT JOIN by switching the order of the tables. But it is good to have options.

The word GROUP BY allows you to group the results by one of three parameters:

col_name- The name of one of the table columnsexpr- A regular expressionposition- A position in the table

You can also have MySQL return the grouped result in ASCcending or DESCending order. And you can create a final line at the end that summarizes the previous lines using WITH ROLLUP. All of these together give us a generic GROUP BY statement that looks like:

GROUP BY (col_name | expr | position) (ASC | DESC) (WITH ROLLUP)For instance, we could select the different types of fish available in our table by:

cursor.execute('SELECT * FROM licenses GROUP BY license')And it will return something like:

[(1, 1, "License to Kill"),

(3, 1, "License to Tango")]Notice that though there are two rows with "License to Kill" in our licenses table, only one is returned by the GROUP BY query.

The clause ORDER BY sorts the results of a query, taking almost the same options as GROUP BY:

ORDER BY (col_name | expr | position) (ASC | DESC)For instance:

cursor.execute("SELECT * from agents ORDER BY name ASC")The query would return:

[(7, "006", "Alec Trevelyan"),

(8, "008", "Bill"),

(3, "002", "Bill Fairbanks"),

(1, "001", "Edward Donne"),

(4, "003", "Jack Mason"),

(2, "007", "James Bond"),

(5, "004", "Scarlett Papava"),

(6, "005", "Stuart Thomas")]Obviously, if you are working in a Python program, you can query whatever data you want from your tables and write it to a text file. That being said, SQL comes with a special key phrase to dump a table of data into a simple CSV file: INTO OUTFILE. Inside your Python scripts, this probably won't get much use, except for testing and debugging, but we might as well see it in action:

The clause INTO OUTFILE is particularly useful for people working in MySQL without Python. But even if you are working with a MySQL database through the Python MySQLdb library, this might be a quick-and-dirty way to write your query results to a file. It works like you might guess:

cursor.execute("""

SELECT * FROM agents ORDER BY id DESC LIMIT 1,5 INTO OUTFILE '/full/path/to/example_agents_file.txt';

""")con.close()