-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 11

/

080 GPUs.jl

134 lines (111 loc) · 4.92 KB

/

080 GPUs.jl

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

import Pkg; Pkg.activate(@__DIR__); Pkg.instantiate()

# # GPUs

#

# The graphics processor in your computer is _itself_ like a mini-computer highly

# tailored for massively and embarassingly parallel operations (like computing how light will bounce

# off of every point on a 3D mesh of triangles).

#

# Of course, recently their utility in other applications has become more clear

# and thus the GPGPU was born.

#

# Just like how we needed to send data to other processes, we need to send our

# data to the GPU to do computations there.

#-

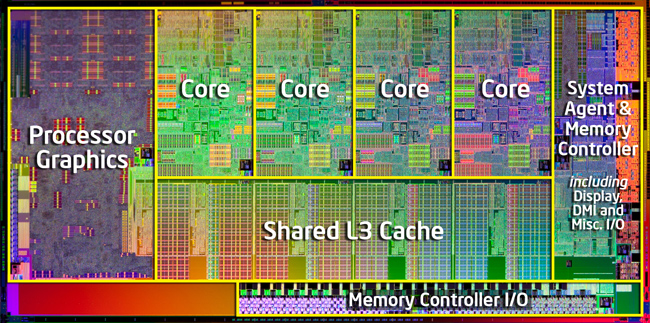

# ## How is a GPU different from a CPU?

#

# This is what a typical consumer CPU looks like:

#

#

#

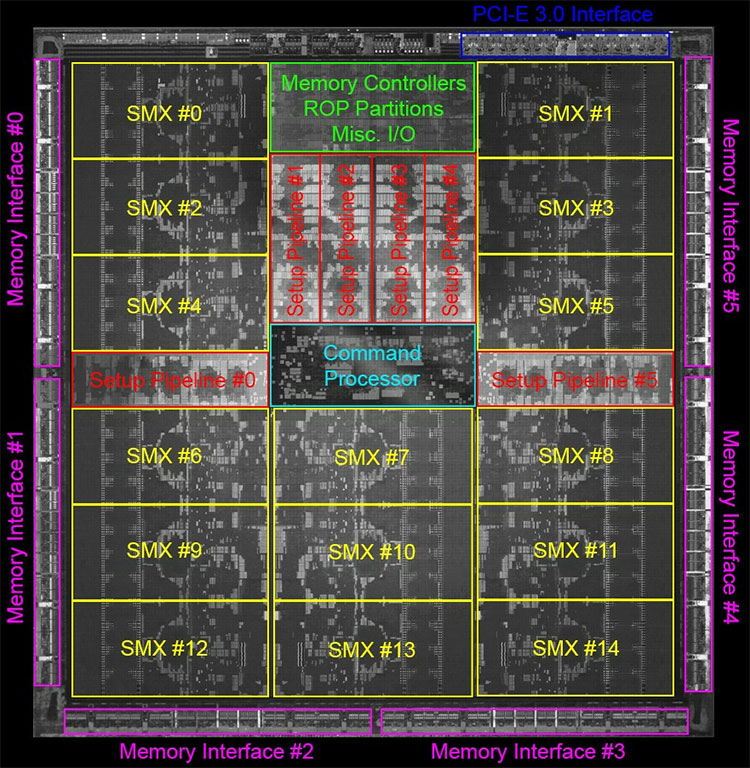

# And this is what a GPU looks like:

#

#

#

# Each SMX isn't just one "core", each is a _streaming multiprocessor_ capable of running hundreds of threads simultaneously itself. There are so many threads, in fact, that you reason about them in groups of 32 — called a "warp." No, no [that warp](https://www.google.com/search?tbm=isch&q=warp&tbs=imgo:1), [this one](https://www.google.com/search?tbm=isch&q=warp%20weaving&tbs=imgo:1).

#

# The card above supports up to 6 warps per multiprocessor, with 32 threads each, times 15 multiprocessors... 2880 threads at a time!

#

# Also note the memory interfaces.

#

# --------------

#

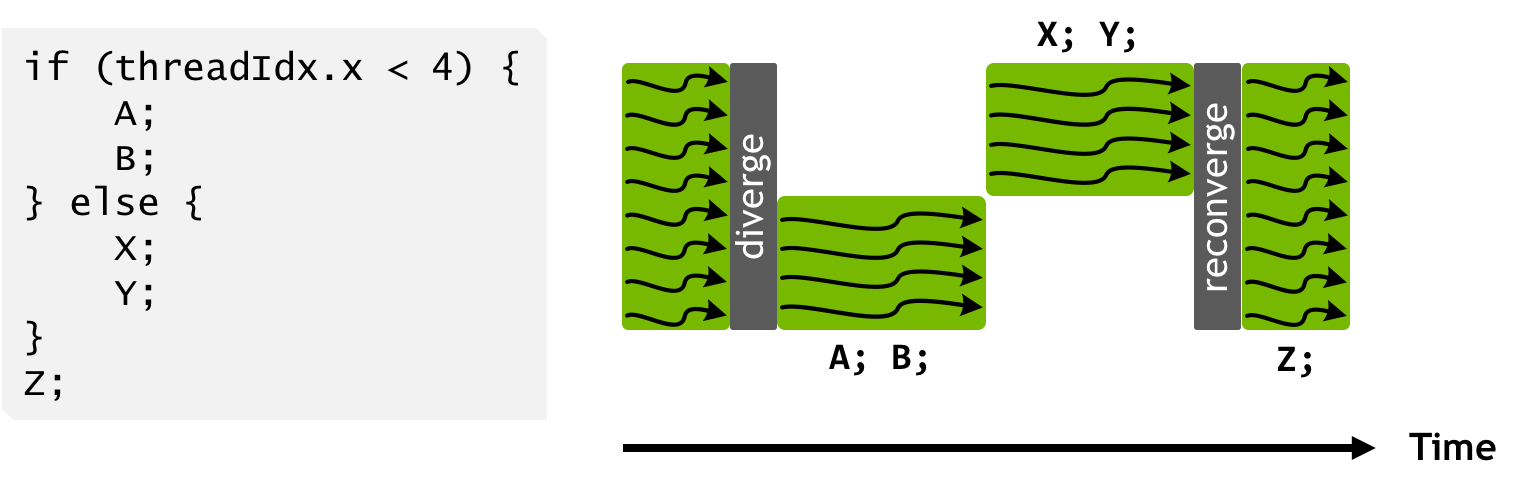

# Each thread is relatively limited — and a warp is almost like a SIMD unit that supports branching. Except it's still only executing one instruction even after a branch:

#

#

#-

# You can inspect the installed GPUs with nvidia-smi:

run(`nvidia-smi`)

# ## Example

#

# The deep learning MNIST example: https://fluxml.ai/experiments/mnist/

#

# This is how it looks on the CPU:

using Flux, Flux.Data.MNIST, Statistics

using Flux: onehotbatch, onecold, crossentropy, throttle

using Base.Iterators: repeated, partition

imgs = MNIST.images()

labels = onehotbatch(MNIST.labels(), 0:9)

## Partition into batches of size 32

train = [(cat(float.(imgs[i])..., dims = 4), labels[:,i])

for i in partition(1:60_000, 32)]

## Prepare test set (first 1,000 images)

tX = cat(float.(MNIST.images(:test)[1:1000])..., dims = 4)

tY = onehotbatch(MNIST.labels(:test)[1:1000], 0:9)

m = Chain(

Conv((3, 3), 1=>32, relu),

Conv((3, 3), 32=>32, relu),

x -> maxpool(x, (2,2)),

Conv((3, 3), 32=>16, relu),

x -> maxpool(x, (2,2)),

Conv((3, 3), 16=>10, relu),

x -> reshape(x, :, size(x, 4)),

Dense(90, 10), softmax)

loss(x, y) = crossentropy(m(x), y)

accuracy(x, y) = mean(onecold(m(x)) .== onecold(y))

opt = ADAM()

Flux.train!(loss, train[1:1], opt, cb = () -> @show(accuracy(tX, tY)))

@time Flux.train!(loss, Flux.params(m), train[1:10], opt, cb = () -> @show(accuracy(tX, tY)))

# Now let's re-do it on a GPU. "All" it takes is moving the data there with `gpu`!

include(datapath("scripts/fixupCUDNN.jl")) # JuliaBox uses an old version of CuArrays; this backports a fix for it

gputrain = gpu.(train[1:10])

gpum = gpu(m)

gputX = gpu(tX)

gputY = gpu(tY)

gpuloss(x, y) = crossentropy(gpum(x), y)

gpuaccuracy(x, y) = mean(onecold(gpum(x)) .== onecold(y))

gpuopt = ADAM()

Flux.train!(gpuloss, Flux.params(gpum), gpu.(train[1:1]), gpuopt, cb = () -> @show(gpuaccuracy(gputX, gputY)))

@time Flux.train!(gpuloss, Flux.params(gpum), gputrain, gpuopt, cb = () -> @show(gpuaccuracy(gputX, gputY)))

# ## Defining your own GPU kernels

#

# So that's leveraging Flux's ability to work with GPU arrays — which is magical

# and awesome — but you don't always have a library to lean on like that.

# How might you define your own GPU kernel?

#

# Recall the monte carlo pi example:

function serialpi(n)

inside = 0

for i in 1:n

x, y = rand(), rand()

inside += (x^2 + y^2 <= 1)

end

return 4 * inside / n

end

# How could we express this on the GPU?

using CuArrays.CURAND

function findpi_gpu(n)

4 * sum(curand(Float64, n).^2 .+ curand(Float64, n).^2 .<= 1) / n

end

findpi_gpu(10_000_000)

#-

using BenchmarkTools

@btime findpi_gpu(10_000_000)

@btime serialpi(10_000_000)

# That leans on broadcast to build the GPU kernel — and is creating three arrays

# in the process — but it's still much faster than our serial pi from before.

#-

# In general, using CuArrays and broadcast is one of the best ways to just

# get everything to work. If you really want to get your hands dirty, you

# can use [CUDAnative.jl](https://github.com/JuliaGPU/CUDAnative.jl) to manually specify exactly how everything works,

# but be forewarned, it's not for the [faint at heart](https://github.com/JuliaGPU/CUDAnative.jl/blob/master/examples/reduce/reduce.jl)! (If you've done CUDA

# programming in C or C++, it's very similar.)