Tern is an optionally typed object oriented language with first class functions and coroutines. It borrows concepts and constructs from many sources including Swift, JavaScript, Java, and Scala amongst others. It is interpreted and has no intermediate representation, so there is no need to compile or build your application.

The interpreter has been built from the ground up, no tools or libraries have been used. As a result the project is small, fully self contained, and can be either embedded or run as a standalone application. Here you will get an overview on how the interpreter works and the language in addition to the debugger and development environment.

Tern is an optionally typed programming language for the JVM and is compatible with all Android variants such as Dalvik and ART. The learning curve is small for anyone with experience of Java, JavaScript, or a similar imperative language. It has excellent integration with the host platform and can leverage the vast ecosystem of the JVM without excessive boilerplate.

The language is ideal for embedding in to an existing application, and is a fraction of the size of similar languages for the JVM platform. In addition to embedding it can be run as a standalone interpreter and has a development environment which allows programs to be debugged and profiled.

Tern programs can be separated in to multiple source files that define the types and functions representing the execution flow. To minimise start times the parsing and assembly of the source is performed in parallel. Once defined the execution graph is joined in to a single executable and static analysis is performed.

The tools and frameworks required to parse and assemble the source code are all custom and written from the ground up with performance and correctness being the primary goals. In most conventional implementations a grammar is used to generate the parser, however for flexibility this implementation processes the grammar at runtime as the program starts, the parser has no prior knowledge of the grammar. This architecture simplifies the implementation and makes it language agnostic.

In the initial phase of compilation the source is passed through a scanner and compressor. This removes comments and command directives from the source text in addition to whitespace that has no semantic value. When the scanner has completed it emits three segments representing the compressed source text, the line numbers the source was scanned from, and a type index classifying the source characters.

To make sense of the source code a custom grammar is required. The grammar used for compilation of the Tern language leverages a custom framework that uses a variant of Bacus Naur Form. It is defined using special rules and literal values that form the basis of a Recursive Descendant Parser.

| Rule | Semantics |

|---|---|

| | | Represents a logical OR |

| * | Represents one or more |

| + | Represents at least once |

| ? | Represents one or none |

| <> | Define a production |

| () | Group productions and literals |

| {} | Group productions where first match wins |

| _ | Represents whitespace |

| [] | Represents a symbol |

| '' | Represents a literal text value |

The formal grammar for the language is defined with these rules, it can be modified to extend the language or tweak existing behaviour.

The lexical analysis phase indexes the source in to a stream of tokens or lexemes. A token can represent one or more primitive character sequences that are known to the parser. For example a quoted string, a decimal number, or perhaps a known keyword defined in the grammar. To categorise the tokens the formal grammar is indexed in to a sequence of literals. If a token matches a known literal then it is classified as a literal. Any given token can contain a number of separate classifications which enables the parser to determine based on the grammar and its context what the token represents.

When this phase of processing completes there is an ordered sequence of classified tokens. Each token will have the line number it was extracted from in addition to a bitmask describing the classifications it has received. It is up to the parser to map these tokens to the formal grammar.

The parser consumes the sequence of categorised tokens produced by the lexer. The parser has backtracking semantics and is performed in two phases. The first phase is to the map the tokens against the grammar and the second phase is to produce an Abstract Syntax Tree.

The final phase of the compilation process is assembly. This process uses a configured set of instructions to map top level grammars to nodes within an execution graph. Configuring a set of instructions facilitates a dependency injection mechanism which is used to build the program.

The syntax tree is traversed in a depth first manner to determine what the instruction dependencies are needed. As the traversal retreats back up from the leafs of the tree to the root instructions are assembled. This process is similar to how many other dependency injection system works.

As a program grows large so to does its complexity. To manage this complexity static analysis is performed across the entire codebase. The level of static analysis performed is up to the developer as types are optional. Access modifiers are also provided to describe intent and visibility of functions and variables.

When leveraging types further qualification can be given in the form of generics. Generics allow the developer to describe the types of parameters that can be used for a specific declaration.

Code evaluation is the process of transforming text to code at runtime. This can be useful when you want to perform some dynamic task. In languages such as Java the reflection framework allows developers to introspect and execute code in a dynamic way. With evaluation you can achieve similar functionality without the boilerplate. Internally evaluations cache the execution trees they represent which eliminates the performance overheads.

let instance = eval("new " + name + "()");The command directive is used to tell command interpreters where the interpreter for the source is located. This is is often called the Shebang directive and is interpreted by common shells like bash. The first line of any Tern source file can contain this command directive.

#!/usr/bin/env snapThe best way to learn any language is through examples. Below is a collection of examples from applications that have been written in Tern. The source code for these examples are available on Github and are free to download.

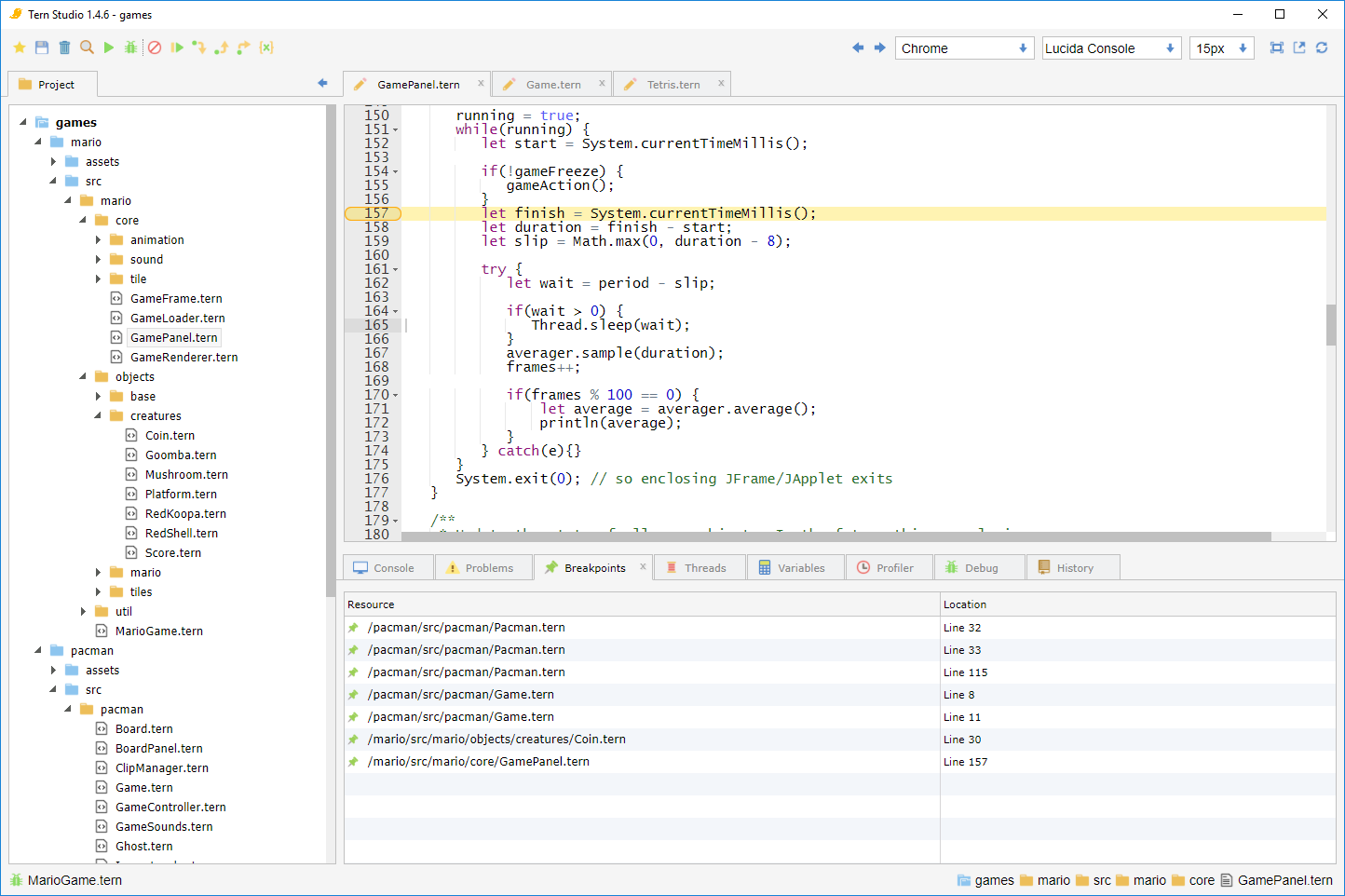

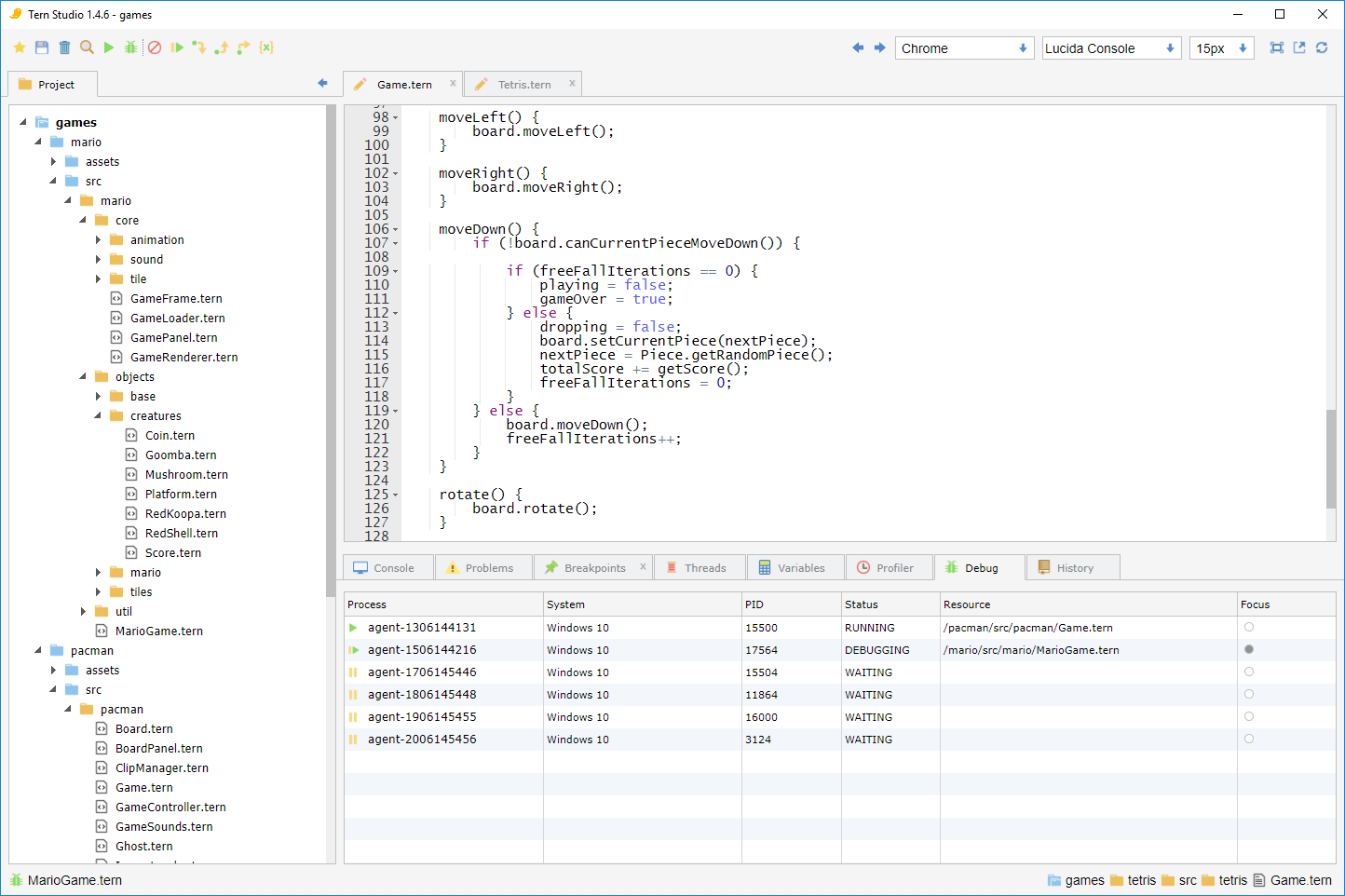

This is a clone of the Mario game comes with the full source code in addition to the images and sounds. It has been written twice, once with full static typing and one with dynamic typing. Below is a YouTube video of the program being run and debugged with Tern Studio.

The statically typed implementation performs type checking throughout.

The dynamically typed implementation is identical to the statically typed implementation without type constraints.

In order to run on Android a framework was required to perform double buffering and map user actions to program behaviour. The Android game framework can be found on Github within this profile.

This is a clone of the Flappy Bird game and is targeted for Android. Below is a YouTube vide of the application being run and debugged remotely with Tern Studio.

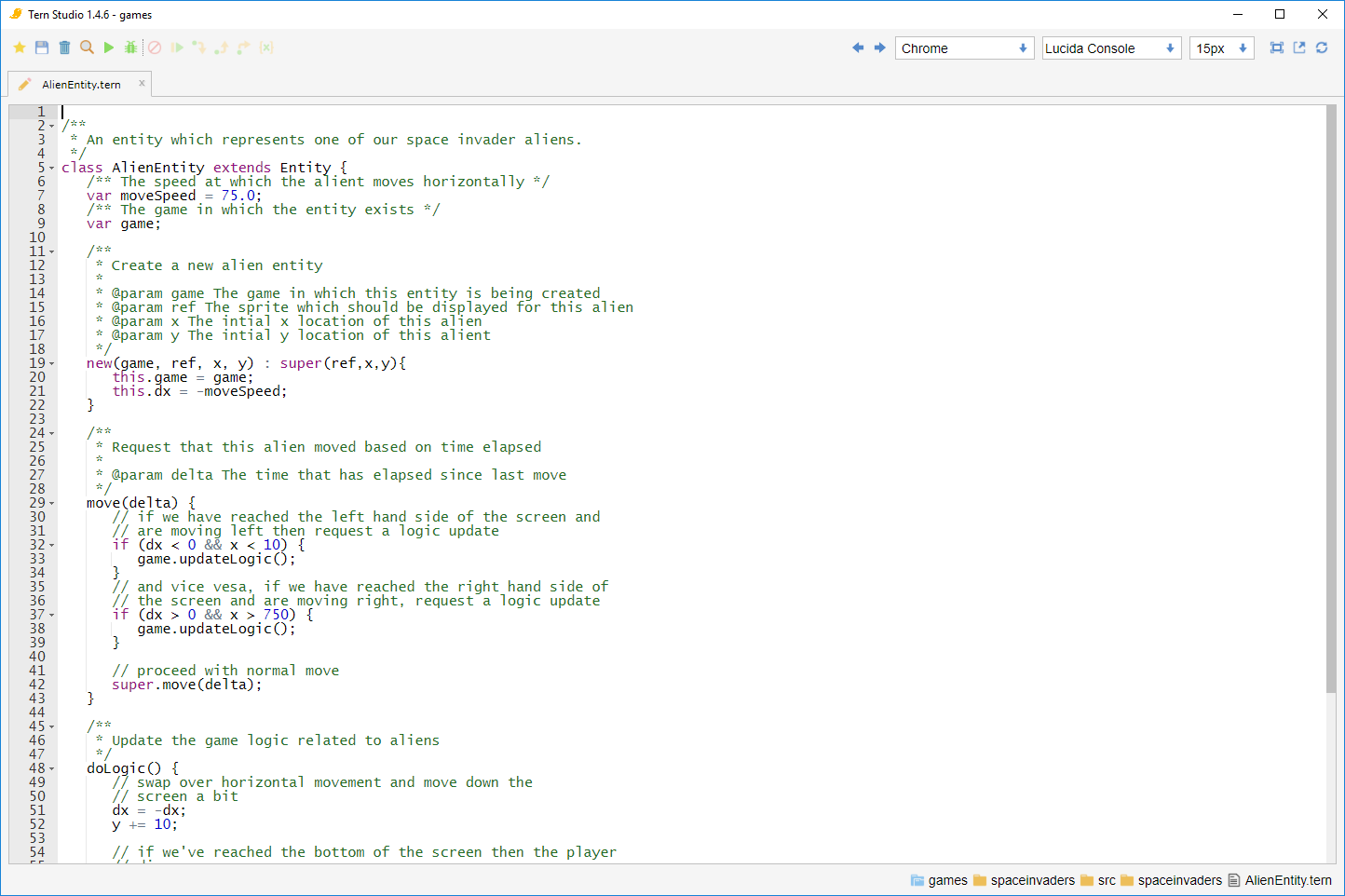

This is a very basic clone of the classic Space Invaders game. The implementation is short but leverages some of the more interesting language features such as async await.

This is a very basic clone of the classic Tetris game. The implementation does not leverage graphics or sounds and shapes are painted on the screen with AWT primitives.

Learning how to code applications with Tern is easy, particularly if you have experience with Java, Javascript, or a similar language. Below you will find various sections illustrating the basics, where you will learn about types, functions, and the various statements and expressions that can be used.

For programs to be useful, we need to be able to work with some of the simplest units of data such as numbers, strings, structures, boolean values, and the like. Support for these basic types is much the same as you would expected for Java, with some additional features such as string templates, map, set, and list literals.

In order to reference values they must be associated with a variable. Variables are declared with the

keyword let or const. A variable can have an optional constraint by declaring a type. If constrained a

variable can only reference values of the declared type.

let v = 22; // v can reference any type

let i: Integer = 22; // i can only reference integers

let d: Double = 22.0; // d can only reference doubles

const c = 1.23; // c is constant, it cannot changeThe most basic type is the simple true or false value, which is called a boolean value.

let a = true; // value a is true

let b = false; // false

let c = Boolean.FALSE; // type constraint of Boolean

let d: Boolean = Boolean.TRUE; // like Boolean d = Boolean.TRUE

let e = Boolean.FALSE; // like Object e = Boolean.FALSEThere are a number of different ways to represent numbers. The most common representation is in decimal format, which is a simple sequence of digits. In addition to the simple decimal notation it can be useful to represent numbers in their binary or hexadecimal format. Below there are examples of some of the numeric literals available to the developer.

let binary = 0b0111011; // binary literal

let hex = 0xffe16; // hexadecimal literal

let int = 11;

let real = 2.13;

let typed: Integer = 22; // integer value 22

let exponent: Double = 1.234e-2; // double with exponentA fundamental part of creating programs is working with textual data. As in other languages, we use the type string to refer to these textual types. Strings are represented by characters between a single quote, a double quote, or a backtick. When characters are between double quotes or backticks they are interpolated, meaning they have expressions evaluated within them. These expressions start with the dollar character. All strings can span multiple lines.

let string = 'Hello World!'; // literal string

let template = "The sum of 1 and 2 is ${1 + 2}"; // interpolated string

let concat = "The sum of 1 and 2 is " + (1 + 2); // concatenation

let multiline = "Details

a) This is an additional line

b) This is another additional line";

let backtick = `A backtick can contain "quotes" and ${expressions}

and can span multiple lines`; To allocate an contiguous sequence of memory an array is required. An array can be created from any type, however arrays of numbers or bytes are created as primitive arrays internally. These primitive arrays provide better integration with streams and buffers.

let array = new String[10]; // array of strings

let bytes = new Byte[11]; // primitive byte[11]

let byte = array[1]; // reference element in array

let matrix = new Long[10][22]; // multidimensional long[10][22];

let long = matrix[2][3]; // reference multidimensionalComplex data structures can be represented with a simple and straight forward syntax. Collection types found in Java such as maps, sets, and lists can be represented as follows.

let set = {1, 2, "x", "y"}; // creates a LinkedHashSet

let list = [1, 2, 3]; // creates an ArrayList

let map = {"a": 1, "b": 2}; // creates a LinkedHashSet

let empty = {:}; // creates an empty map

let mix = [1, 2, {"a": {"a", "b", [55, 66]}}]; // mix collection types

let multiline = {

name: "John Doe",

address: {

city: "Unknown",

state: "California"

},

age: 33

};

let ascending = [0 to 9]; // range of increasing numbers

let descending = [0 from 9]; // range of decreasing numbersOperators are special symbols that perform specific operations on a set of operands. The operators available are those found in most conventional imperative languages, such as those to perform algebra or compare values.

Arithmetic operators are used in mathematical expressions in the same way that they are used in algebra. These operations can be grouped and order can be specified using braces.

let a = 10;

let b = 20;

let c = a + b; // add is 30

let d = b - a; // subtract is 10

let e = b / a; // divide is 2

let f = a * b; // multiply is 200

let g = b % a; // modulus is 0

let h = a++; // a is 11 and h is 10

let i = b--// b is 19 and i is 20

let j = --a; // a is 10 and j is 10

let k = ++b; // b is 20 as is k

let l = 1 / ((a + b) * 10)Bitwise operators are used to manipulate numbers, typically integers, at the byte level. They do so by change the binary representation of the value.

let a = 0b00111100;

let b = 0b00001101;

let c = a & b; // bitwise and, c is 00001100

let d = a | b; // bitwise or, d is 00111101

let e = a & b; // bitwise xor, e is 00110001

let f = ~a; // f is 11000011

let g = f >> 2; // f is 00110000

let h = f << 2; // h is 11000000

let i = f >>> 2; // unsigned shift, i is 00110000Both the arithmetic and bitwise operators have priority and are evaluated in a specific order if no braces are used to group or enforce order. The evaluation order applied is shown in the table below.

| Order | Operator | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ** | Exponential operator |

| 2 | / | Divide operator |

| 3 | * | Multiply operator |

| 4 | % | Modulus operator |

| 5 | + | Addition operator |

| 6 | - | Subtraction operator |

| 7 | >> | Signed shift right operator |

| 8 | << | Shift left operator |

| 9 | >>> | Shift right operator |

| 10 | & | Bitwise AND operator |

| 11 | | | Bitwise OR operator |

| 12 | ^ | Bitwise XOR operator |

Relational operators are used to make comparisons, such as equal to, not equal to, greater than, less than.

let a = 10;

let b = 20;

let c = a == b // equal operator, c is false

let d = a != b; // not equal operator, d is true

let e = a > b; // greater than operator, e is false

let f = a < b; // less than operator, f is true

let g = a <= b; // g is false

let h = a >= b; // h is trueLogical operators are typically used to combine multiple relational operations in to a single boolean result.

let a = 1;

let b = 3;

let c = true;

let d = false;

let e = a && b; // e is false

let f = a || b; // f is true

let g = !d; // not operator, g is true

let h = b > a && a == 1; // logical and of, h is true

let i = b > a && a != 1; // i is falseConditional statements are used to perform different actions based on different conditions.

The if statement is used to specify a group of statements to execute if a statement is true.

const a = 2;

const b = 3;

if(a < b) { // true

println("a > b"); // prints as a < b

}The else statement is used to specify a group of statements to execute if a statement is false.

const a = 2;

const b = 3;

if(a >= b) { // false

println("a >= b");

} else {

println("a < b"); // prints as a < b

}The unless statement is used to specify a group of statements to execute if a statement is false.

const a = 2;

const b = 3;

unless(a > b) { // false

println("a > b"); // prints as a < b

}The assert statement is used to determine if an expression evaluates to true or false. If the expression evaluates to true the operation has no effect, otherwise an assertion exception is thrown.

const a = 2;

const b = 3;

assert a < b;

assert a > b; // assert exceptionThe debug statement is used to suspend any attached debugger if and expression evaluates to true. This can be useful if there is a specific part of the program that you want to evaluate given a known state of execution. It is similar to the debugger statement for JavaScript with the addition of logic predicate the suspension.

debug a * b > 4; // suspend the debugger if trueTo make statements more concise there is a ternary operator.

let a = 2;

let b = 3;

println(a >= b ? "a >= b" : "a < b"); // prints a < bThe null coalesce operator is similar to the ternary operator with one exception, the evaluation is whether a value is null.

let a = null;

let b = 3;

println(a ?? b); // prints bLoops are used to perform a group of statements a number of times until a condition has been satisfied.

The while statement is the simplest conditional statement. It repeats a group of statements while the condition it evaluates is false.

let n = 0;

while(n < 10) { // conditional loop

n++;

}The until statement is similar to the while statement but loops while the condition is false. It repeats a group of statements until the condition it evaluates is true.

let n = 0;

until(n >= 10) { // conditional loop

n++;

}The for statement is typically used to count over a range of numeric values. It contains three parts, a declaration, a condition, and an optional statement which is evaluated at the end of the loop.

for(let i = 0; i < 10; i++){ // loops from 1 to 10

if(i % 2 == 0) {

continue; // continue loop

}

println(i); // prints only odd numbers

}The for in statement offers a simpler way to iterate over a range of values, a collection, or an array.

let list = [35, 22, 13, 64, 53];

for(e in list){ // iterates over the list

println(e);

}

for(e in 0..9) { // iterates from 0 to 9

if(e == 7) {

break; // exit loop when e is 7

}

println(e); // prints from 0 to 6

}

for(i in 0 to 9) { // iterates from 0 to 9

println(i);

}

for(i in 0 from 9) { // iterates from 9 to 0

println(i)

}The loop statement offers a way to specify an infinite loop, it does not evaluate any condition.

let n = 0;

loop { // infinite loop

if(n++ > 100) {

break;

}

}Exceptions are used to indicate an error has occurred. It offers a simple means to return control to a calling function, which can then handle the error. Typically an exception object is thrown, however it is possible to throw any type.

In order to catch an exception the throwing statement needs to be wrapped in a try catch statement. This statement basically allows the program to try to execute a statement or group of statements, if during execution an exception is thrown then an error handling block is executed.

try {

throw new IllegalStateException("some error");

} catch(e: IllegalStateException) {

e.printStackTrace();

}The finally statement is a group of statements that are always executed regardless of whether an exception is thrown.

try {

throw "throw a string value";

} catch(e) {

println(e);

} finally {

println("this always runs");

}Functions group together control structures, operations, and method calls. These functions can then be called when needed, and the code contained within them will be run. This makes it very easy to reuse code without having to repeat it within your script.

The most basic type of function is declared with a name and a specific number of parameters. Such a method can then be called using the declared name by passing in a right number of arguments.

let r = max(11, 3, 67); // r is 67

func max(a, b) {

return a > b ? a : b;

}

func max(a, b, c) { // function overloading

return a < b ? max(a, c) : max(b, c);

}In order to bind invocations to the correct function implementation it can be declared with optional type constraints. These type constraints will ensure that variables of a specific type will be bound to the correct implementation.

let x: Double = 11.2;

let y: Integer = 11;

let z: String = "11";

dump(x); // prints double 11.2

dump(y); // prints integer 11

dump(z); // prints string 11

dump(true); // type coercion to string, prints string true

func dump(x: Integer) {

println("integer ${x}");

}

func dump(x: Double) {

println("double ${x}");

}

func dump(x: String) {

println("string ${x}");

}At times it can be useful to provide a large number of arguments to a function. To achieve this the last parameter can be declared with a variable argument modifier.

let result = sum(0, 13, 44, 234, 1, 3);

func sum(offset, numbers...){ // variable arguments

let size = numbers.size();

let sum = 0;

for(let i = offset; i < size; i++){

sum += number;

}

return sum;

}When the number of arguments increases for a function it can be difficult to determine which values map to the parameters they represent. Naming arguments offers a means for the static analyzer to ensure that your arguments are mapped to the correct parameters.

func purchaseProduct(product, price, quantity, customer, date) {

basket.add(product, quantity);

account.deduct(quantity * price);

}

purchaseProduct(

product: 'TV',

price: 100.0,

quantity: 2,

customer: 'Bob',

date: '2019-01-01')A closure is an anonymous function that captures the current scope and can be assigned to a variable. This variable can then act as a function and can be called in the same manner.

const square = (x) -> x * x;

const cube = (x) -> square(x) * x;

cube(2); // result is 8

const printAll = (values...) -> {

for(var e in values) {

println(e);

}

}

printAll(1, 2, 3, 4); // print all valuesCurrying is a technique that allows you to cascade calls across functions and closures. This can be expressed in an idiomatic way as functions are first class citizens. Below is an example of how to curry with functions and closures.

func sumMax(x) {

return (a, b) -> x + Math.max(a,b);

}

func mathOps(x){

return {

'+': (y) -> x + y,

'-': (y) -> x - y,

'*': (y) -> x * y,

'/': (y) -> x / y

};

}

assert sumMax(1)(3, 4) == 5;

assert mathOps(10)['+'](2) == 12

assert mathOps(10)['-'](2) == 8;

const sumMaxTen = sumMax(10);

assert sumMaxTen(2, 3) == 13;A function handle is simply a way to reference an existing function as a closure. Function handles can represent constructors or functions that are in scope. For example take the constructor for a string, it is quite possible to execute the following.

['a', 'b', 'c'].iterator.forEachRemaining(this::println)Here we are calling the println function with the item passed to the function. This function is represented as a function handle that takes a string. A function handle can represent a static or an instance function. For example:

class Formatter {

public static upper(s: String) {

return s.toUpperCase();

}

}

['a', 'b', 'c'].stream().map(Formatter::upper).forEach(this::println);Generics can be used to qualify the arguments that can be passed to a function. They are useful when the static analyser verifies the program as it ensures arguments and return types match the declared qualifiers.

func abs<T: Number>(nums: T): List<T> {

let result: List<T> = [];

for(num in nums) {

let abs = num.abs();

result.add(abs);

}

return result;

}

let list: List<Double> = abs<Double>(-1.0, 2.0, -3.0);

assert list[0] == 1;

assert list[2] == 2;It is often useful to suspend execution of a function in order to return a result. Typically this requires a great deal of effort from the developer. Coroutines allow an idiomatic means of suspending the execution of a function which can be resumed at the point of suspension. This allows for complex reactive iteration to be performed with minimal effort. For example take a Fibonnaci sequence.

func fib(n){

let a = 1;

let b = 2;

until(n-- <= 0) {

yield a; // function is suspended here

(a, b) = (b, a + b);

}

}Asynchronous functions can be implemented with the async and await modifiers. This is similar to a standard Coroutine however this paradigm will allow the execution of the program to fork in two different threads of execution.

async loadImage(n: String): Promise<?> {

if(!cache.contains(n)) {

return await ImageIO.read(n);

}

return cache.get(n); // no need to go async

}All async functions can cascade such that if an async function calls another it is suspended until the function being called completes, at which point it will resume from the call site. For convenience closures can also be asynchronous.

let loadImage = async (n: String) -> ImageIO.read(n);Here there is no need to specify the await keyword as expression based asynchronous closures have an implicit await. For closures that have more than a single expression you must specify which statements are asynchronous.

let loadImage = async (n: String) -> {

if(!cache.contains(n)) {

return await ImageIO.read(n);

}

return cache.get(n); // no need to go async

}Blank parameters allow you to specify an argument that is not needed or can be ignored.

func create<T>(type: T): T {

return cache.computeIfAbsent(type.name, (_) -> new T());

}In any object oriented language types are required. A type is basically a way to define and encapsulate variables and functions within a named scope. All types can have generic parameters allowing the static analyser to verify interactions with the type.

The type system for Tern is independent to the type system native to the JVM. To integrate with the JVM type system ASM byte code generation and Dex code generation are leveraged to create bridges between native types and those constructed from the program execution flow.

A class is the most basic type. It contains variables, and functions that can operate on those variables. Once declared a type can be instantiated by calling a special function called a constructor. There are two primary categories of class, the abstract class and the concrete class. An abstract class represents a generic concept and as such cannot be instantiated. Below is an example of an abstract class.

abstract class Shape {

let origin: Point;

new(origin: Point) {

this.origin = origin;

}

/**

* Draw the shape to the provided graphics. Each

* shape will be drawn from the origin.

*

* @param g the graphics to draw with

*/

abstract draw(g: Graphics);

class Point { // inner class

const x;

const y;

new(x, y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

}

}A concrete class represents an whole object or entity and unlike abstract classes it can be instantiated. To leverage methods and state from other classes inheritance is possible. Below we can see how a square inherits state and a method from the abstract shape class.

class Square extends Shape {

private let width: Integer;

private let height: Integer;

new(origin: Point, width: Integer, height: Integer): super(origin) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

/**

* Draw a square at the origin.

*

* @param g the graphics to draw on

*/

override draw(g: Graphics) {

g.drawSquare(origin.x, origin.y, width, height);

}

}By default functions defined in the body of a class are public. This means any scope where an instance of the class is accessible can call this public method. The opposite is true for private methods. Private method can be called only within the body of the class.

Below is a list of the modifiers that can be applied to functions defined within the body of a class.

| Modifiers | Description |

|---|---|

| public | Public functions and variables are visible in all scopes |

| private | Private functions are visible only within the class body |

| abstract | Abstract functions have no implementation |

| override | An override reflects replacing a super class function |

| static | Static methods can be called without an instance |

| async | Async functions can be suspended and resumed concurrently |

An enumeration is a type that specifies a list of constant values. This values are constant and are instances of the enum they are declared in.

enum Color {

RED("#ff0000"),

BLUE("#0000ff"),

GREEN("#00ff00");

let rgb;

new(rgb) {

this.rgb = rgb;

}

}

let red = Color.RED;

let blue = Color.BLUE;A trait is similar to a class in that is specifies a list of functions. However, unlike a class a trait does not declare any variables and does not have a constructor. It can be used to add functions to a class.

trait NumberFormat<T: Number> {

/**

* Round to number to a specific number of decimal

* places or to an integer.

*

* @param a places to round to

*/

round(a): T;

format(a: T) {

return round(a);

}

}

class DoubleFormat with NumberFormat<Double> {

let places: Integer;

new(places: Integer) {

this.places = places;

}

override round(a: Double) {

return a.round(places);

}

}

class IntegerFormat with NumberFormat<Integer> {

override round(a: Integer) {

return a;

}

}A module is collection of types, functions, and variables. It is similar to enclosing a script within a named type. Modules are useful in providing constructs such as singletons.

module ImageStore {

private const cache = {:};

public find(name) {

return cache.get(name);

}

private cache(name, image) {

cache.put(name, image);

}

} All types and functions can accept generic parameters. Geenerics in are basically additional parameters than can be applied to a function or type in order to improve static analysis. The static analyser will perform projections on any generic entity to determine types when generics cascade. Below is an example of how generic parameters applied to a hash map can enable the compiler to perform projections to determine the actual types from a stream of values.

let map: Map<?, Number> = HashMap<?, Number>();

map.get('x').iterator(); // compile error

map.get('x').intValue(); // success

map.values().stream().findFirst().get().toUpperCase(); // compile error

map.values().stream().findFirst().get().doubleValue(); // successGeneric projections are also performed on type hierarchies such that it is possible to determine the actual types for all functions and properties. Below is an example of how static analysis can use a generic declaration to determine the actual types for the functions invoked.

trait Repository<A, B> {

findOne(key: A): B;

findAll(): Map<A, B>;

}

class Person {

const name: String;

const address: String;

new(name: String, address: String) {

this.name = name;

this.address = address;

}

getName() {

return name;

}

}

trait PersonRepository<A> with Repository<A, List<Person>> {

findPerson(key: A): List<Person>;

}

let repo: PersonRepository<String> = // ...

repo.findAll().values().stream().findFirst().get().getName(); // compile error

repo.findAll().values().stream().findFirst().get().stream().findFirst().get().getName(); // success

repo.findPerson("john").stream().findFirst().get().getName(); // successAnnotations can be applied to any type and do not need to be declared. These are useful when you need to determine the behaviour of a type and its methods through introspection.

@ComponentPath(path: '/images')

class ImageService {

@Path(match = "/{path}")

@Method(verb: 'GET')

@ContentType(value: 'image/png')

getImage(@Param(name: 'path') path) {

return ImageIO.read(path);

}

}It can often be useful to alias types for readability, particularly when generics are involved. An alias is not a new type but rather a new name for a known type.

import util.concurrent.ConcurrentHashMap;

type Bag<T> = ConcurrentHashMap<String, T>();

func bagOf<T: Number>(nums...: T): Bag<T> {

let bag: Bag<T> = new Bag<T>();

for(num in nums){

bag.put(`${num}`, num);

}

return bag;

}The uniform access principle of computer programming was put forth by Bertrand Meyer in his book called Object Oriented Software Construction. It states all services offered by a module should be available through a uniform notation, which does not betray whether they are implemented through storage or through computation. An example of this is typical getter and setter property methods but applies to any method that does not require arguments.

class Person {

private const firstName;

private const surname;

new(firstName, surname) {

this.firstName = firstName;

this.surname = surname;

}

getFullName() {

return "${firstName} ${surname}";

}

}

let person = new Person("John", "Doe");

assert person.fullName == 'John Doe';Uniform access applies to all implemented types as well as any external dependencies imported regardless of their origin, for example the Java class libraries.

In order to access the Java types available they can be imported by name. Once imported the type can be instantiated and used as if it was a script object. In addition to importing types, functions can also be imported by using a static import.

import static lang.Math.*; // import static functions

import security.SecureRandom;

const random = new SecureRandom(); // create a java type

const a = random.nextInt(40);

const b = random.nextInt(40);

const c = max(a, b); // Math.max(a, b)

println(c); // prints the maximum randomTo avoid name collisions it is also possible to import types with aliases. Additionally an imports visibility can be encapsulated within a module so that it is only available in that module.

import util.concurrent.ConcurrentHashMap as Bag;

module ImageStore {

import aws.image.BufferedImage as Image;

import aws.Graphics;

public paint(g: Graphics) {

// ...

}

}Imports can be grouped from the same package using braces. Below is an example of import groups.

import util.concurrent.{ ConcurrentHashMap, CopyOnWriteArrayList };

import util.{ Map, Set, List };For interfaces that have only a single method a closure can be coerced to that interface type. This makes for a much simpler and concise syntax similar to that offered by Java closures.

const set = new TreeSet(Double::compare);

set.add(1.2);

set.add(2.3);

set.add(33.4);

set.add(4.55);

set.add(2);

for(entry in set){

println(entry);

}To leverage the large array of frameworks and services available on the Java platform any Java type can be instantiated, and any Java interface can be implemented.

class DoubleComparator with Comparator{

override compare(a,b){

return Double.compare(a,b);

}

}

let comparator = new DoubleComparator();

let set = new TreeSet(comparator);

set.add(1.2);

set.add(2.3);

set.add(33.4);

set.add(4.55);

set.add(2);

for(let entry in set){

println(entry);

}To be productive in any language there needs to be a way to write, evalute and debug applications. The development environment is free to use and can be used in any standard web browser supporting HTML 5. Alternatively this development client can be run as a standalone application.

To run scripts as a standalone application you can download the interpreter. The interpreter requires Java to be installed on the host machine. Once you have downloaded the interpreter you can begin running scripts right away. All you need to do is specify the script file relative to the current directory.

| Platform | Description | Download |

|---|---|---|

| Java | Command line interpreter for Java and Android | Download |

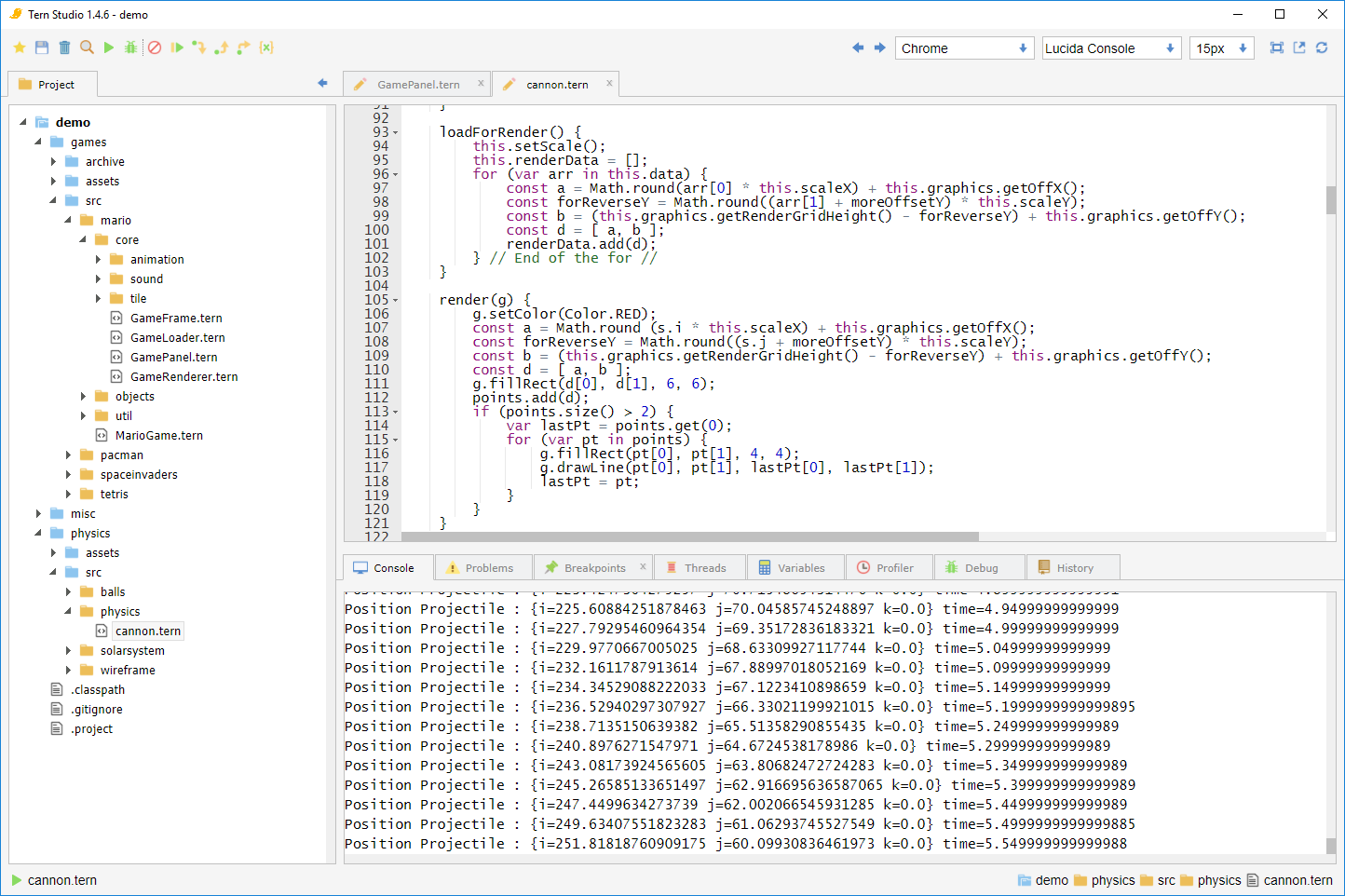

The development environment, Tern Studio, is written with HTML5 and TypeScript. It comes packaged as a standalone application leveraging the Chrome Embedded Framework. Running an application from Tern Studio is as simple has pressing the play button. This will initiate a bootstrapping process where the interpreter is downloaded in to a harness once this bootstrapping process has completed the source program is downloaded and executed. Stepping through the code can be done by setting break points.

| Platform | Description | Download |

|---|---|---|

| Windows | This build uses Chrome Embedded Framework compatible with 64-bit Windows | Download |

| Linux | This build uses Chrome Embedded Framework compatible with 64-bit Linux | Download |

| Mac | This build uses Chrome Embedded Framework compatible with 64-bit Mac | Download |

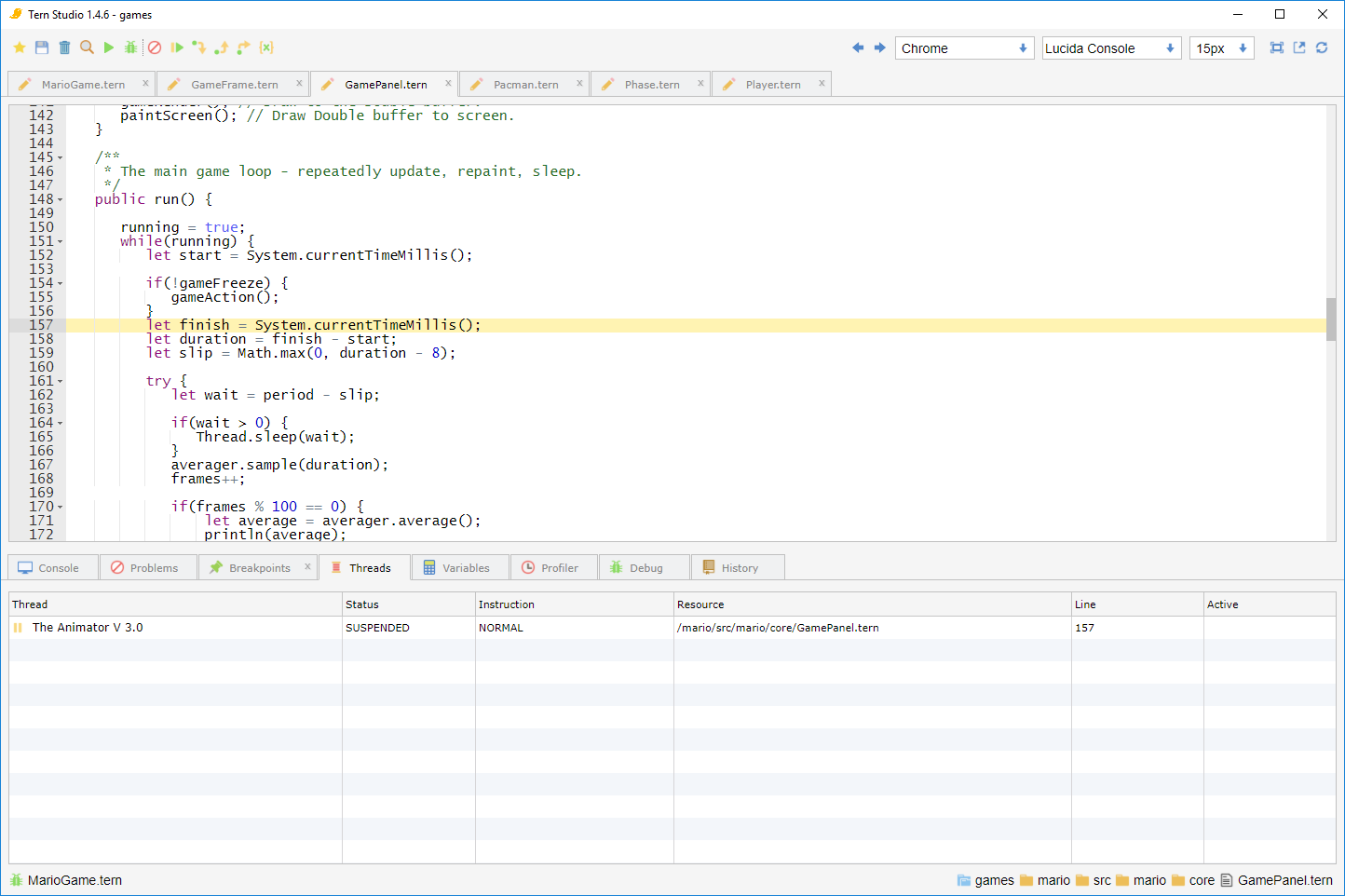

A breakpoint forces the debugger to suspend at a particular line when execution flow arrives at that line. Once suspended the developer can step in, out or over the statements.

All output from the application is captured in the console and displayed. This console is a scrolling window and will keep only the most recent history up to a configurable number of lines.

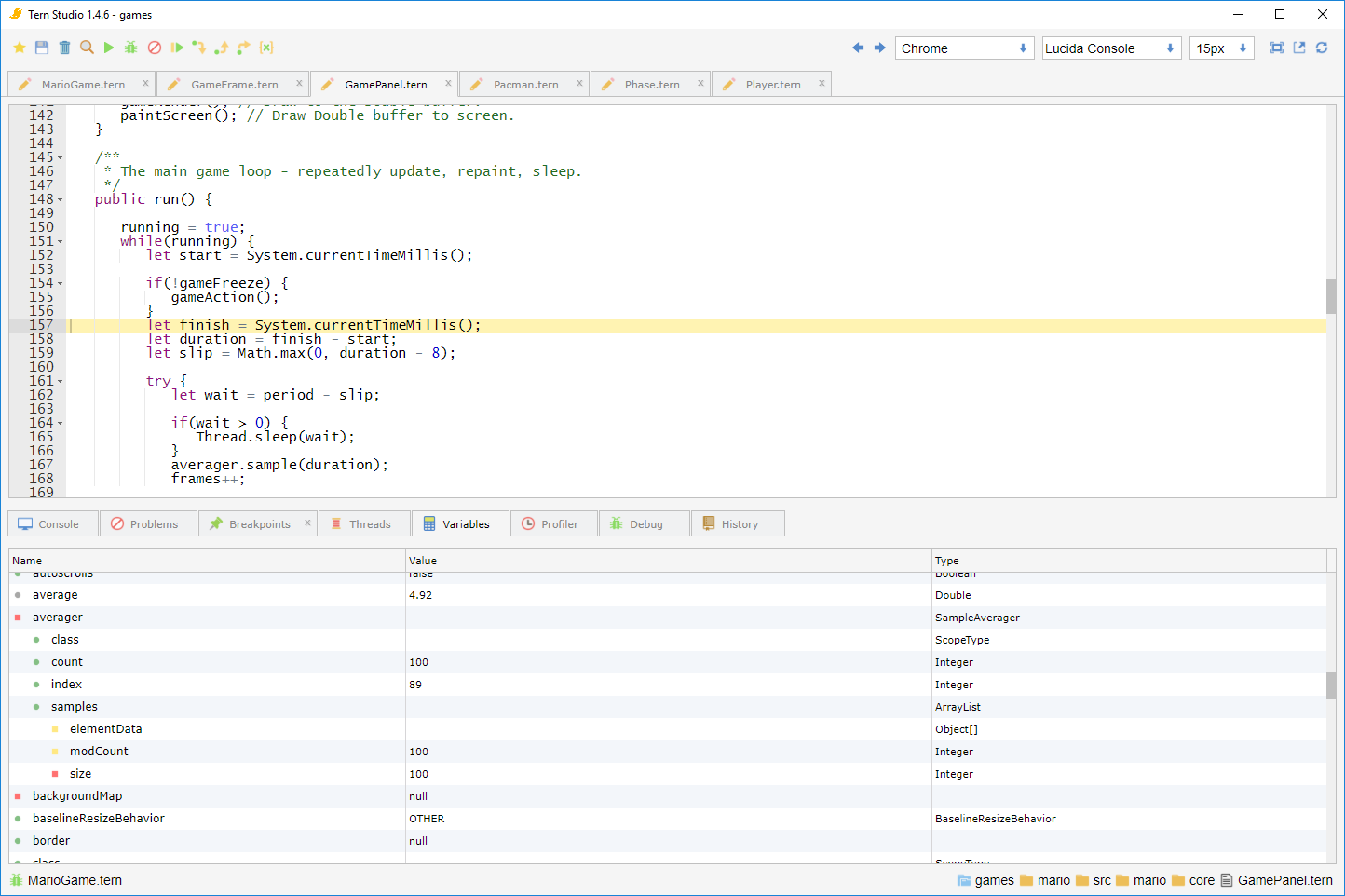

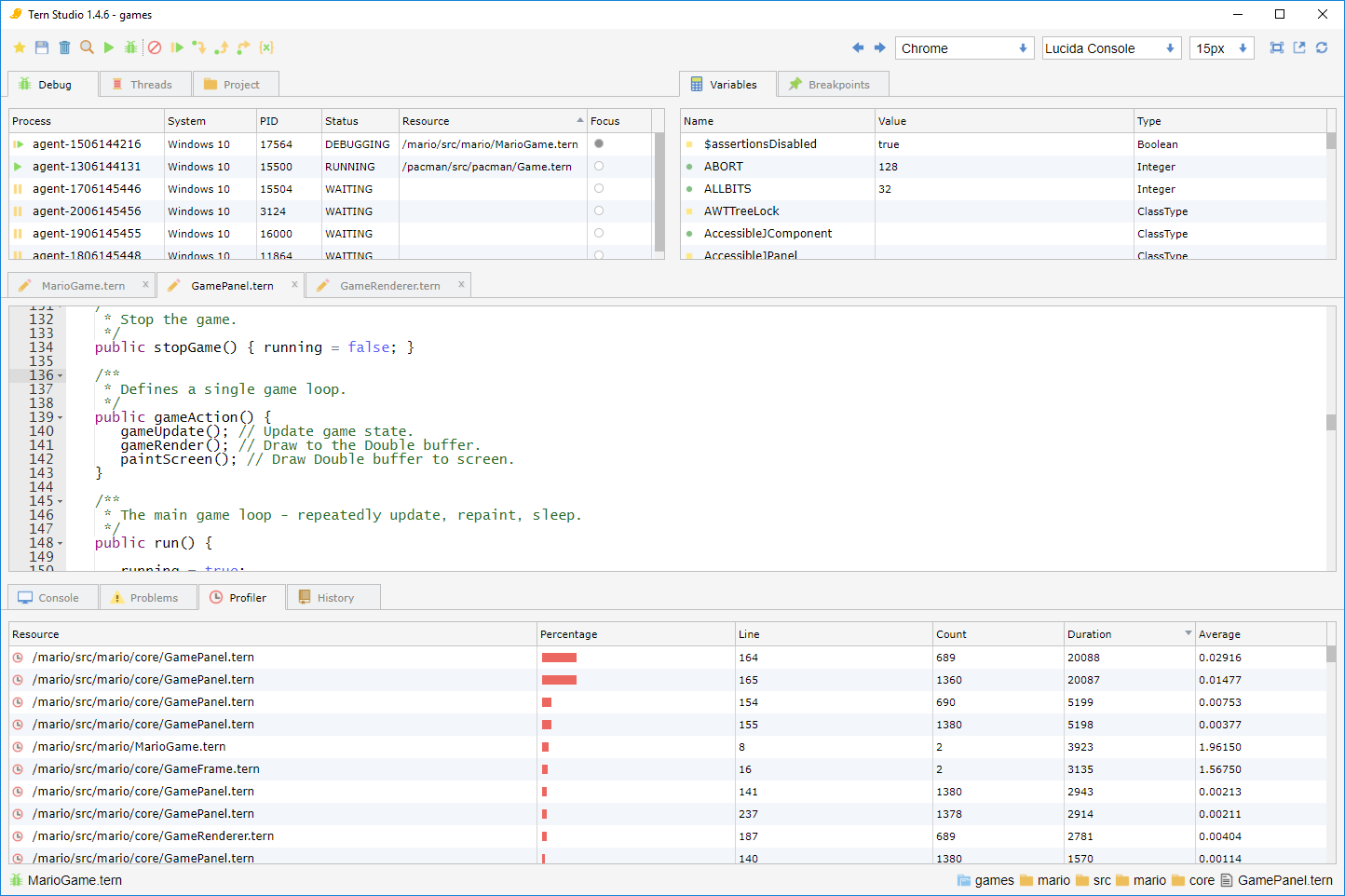

When execution is suspended it is possible to evaluate expressions and look at variables on the stack and in the surrounding scope. These variables can be navigated by clicking through references.

At any time multiple threads may be suspended. A thread view is provided so that the developer can select the thread to debug and also to view the stack frames.

If there are multiple applications running from the development environment focus can only be given to one. It is possible to switch focus through the process view. Once focused an application can be debugged or terminated.

To capture as much relevant information on a single screen the debug perspectived can be used. This will allow the developer to see the threads and variables as well as the console.

When editing it can be useful to see the full screen. This perspective can be achieved by double clicking on the tab in focus.

The development environment can act as a debug service. As such it is possible to connect to a debugger and push code and debug information. To do this you simple need to embed the debug agent in to your application.

Full compatibility is provided for Android. A basic JIT is also provided to reduce the overhead of reflection and to allow types to be extended.